Golden Handcuffs

To Break or To Stay: Life in Sub Optimality and Comfort

In the world of tech and perhaps greater white collar work, there is a common situation that many find themselves in: the work is dull but the compensation is lucrative, which may include high salaries, vested stock options, ancillary fitness benefits, and health insurance. This means that despite the weekday work hours inspiring meaninglessness, dispassion, and tiredness, professionals find it difficult to leave their positions. Thus, a dilemma is raised: should the professional leave the current position and give up all the lucrative benefits or should the status quo be maintained? This is aptly named the “Golden Handcuffs.”

For an outside observer looking in, the Golden Handcuffs quandary seems fairly trivial: why not just quit the job and chase the dream? After all, the successful bunch worshipped in society- celebrities, gritty founders, and professional athletes- whose stories are almost common knowledge, seem to practise and preach this gospel. But, they have the benefit of hindsight and survivorship bias. It is certainly easier to say “just quit” than it is to actually quit and follow whatever the dream is- just ask the millions of unknowns who tried, failed, and will never have their stories glamorized in media. Once fantasy is met by reality, there are very consequential factors that may no longer be ignored, which may include uncertainty, financial security, lifestyle adjustment, and internal confidence from perceived social status movement. Golden Handcuffs may feel even more tight under the cognitive biases of loss aversion- the pain of losing being twice as powerful than the pleasure of winning. Theorizing about action is far different than enacting the action theorized.

To deepen the difficulty of making a decision, the Golden Handcuff scenario is, by nature, a very privileged position to be in. In a world of rising living costs, black swan economic disasters, and unique medical and familial circumstance, which may all gradually or suddenly drain monthly income, meaninglessness while having a lucrative compensation is at the terminal of things to be sympathetic towards. And rightly so. Passion is not as pressing when the necessities needed to support it- stable living, food security, healthy relationships- are not guaranteed.

Despite its common application for those in this privileged position, the themes in Golden Handcuffs apply to a wider demographic than traditionally portrayed. It is relative to the personal evaluation of the comfort to interest tradeoff in a given occupation; it just so happens that metrics like total compensation are quantitative and easily used to set a hard definition for what Golden Handcuffs is. The golden quality is always in the eye of the beholder; handcuffs which sufficiently fund hobbies, lifestyles, and relationships may all be golden, iron, and diamond at the same time based on frame of reference. Anyone can wear golden handcuffs and be in this dilemma.

It further encompasses a wide number of situations and may not be binary (stay vs leave) nor well defined; however, in its very essence, Golden Handcuffs distills into a two part question: how is meaning in life measured and how is this meaning maximized? Based on the answer informed by an infinite combination of individualistic circumstance, experience, and psychological frameworks to the former question, the parameters and constraints in the latter question can be better defined and an answer be closer reached. Depending on these answers, Golden Handcuffs may not be applicable. For example: if meaning in life is strictly defined along the vectors of providing for family and being in the company of loved ones, the main motivator of work would then be for financial incentives to maintain a joyous family life and a stable lifestyle. While Golden Handcuffs may be present, one may be contently handcuffed with the outsized benefits of an uninteresting occupation. Another assumption that underlies the Golden Handcuff dilemma is that there is desire to optimize for meaning and that the current circumstances do not achieve this desire; otherwise, there is no Golden Handcuff, just a golden situation.

The privileged circumstances and the comfortable benefits of being in this situation certainly aligns the dilemma of Golden Handcuffs with the Region-Beta Paradox, which in its original definition is the phenomenon that individuals recover more quickly from intense distress when compared to mild distress. Studied through experiments where participants’ reactions to various levels of transgressions are measured and compared, the Region-Beta Paradox cites the trigger of “psychological processes that attenuate distress” from catastrophe (ie: divorce and disease) but not from mild inconvenience (ie: slow elevators) as a contributing factor. Mild distresses simply do not reach the threshold in which our intense rationalization, solution finding, and survival instincts kick in. As such, it may be more optimal to be in more distressing settings than it is their mild counterparts.

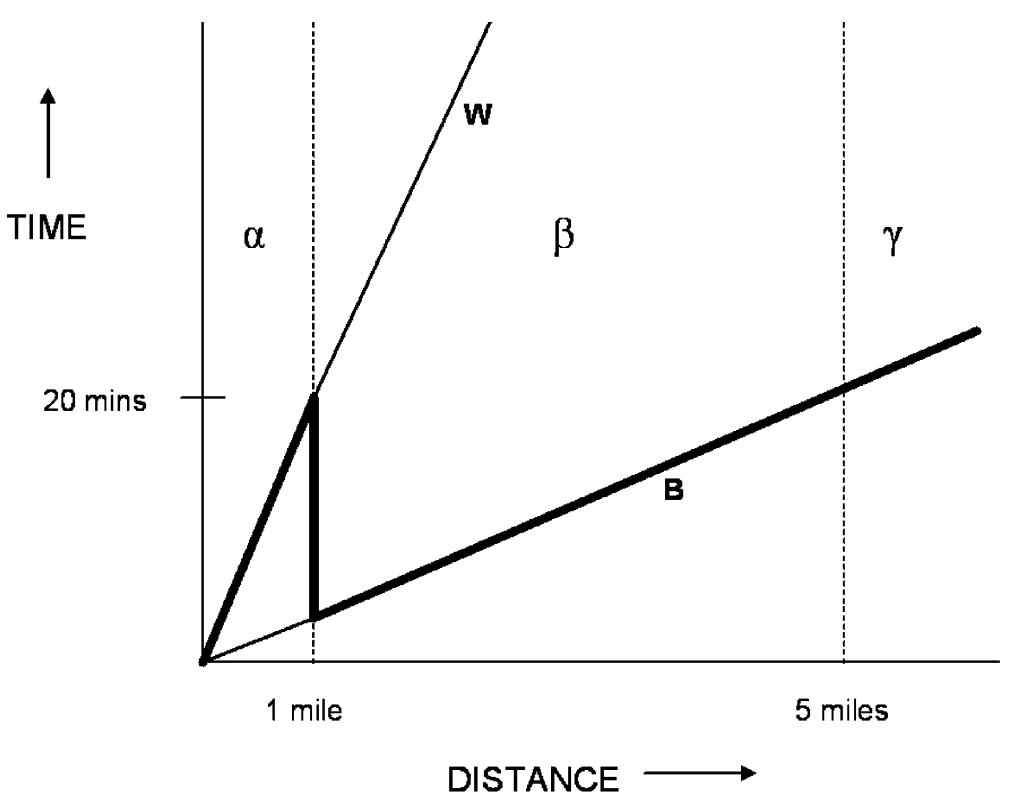

To illustrate this idea, the example commonly cited is the relation between time and distance for a person electing to walk or bike to a certain destination if the distance travelled is within or beyond 1 mile. When we compare the alpha and the beta region, the person takes less time travelling a further distance; it is more optimal to bike to the destination no matter how far the distance travelled is. Here, biking is the response to the intense > 1 mile travelled distress, while walking is the response to the mild < 1 mile travelled distress.

In relation to the Region-Beta Paradox, Golden Handcuffs represents the alpha region: the pain of meaningless work is sufficiently mitigated by the various lucrative benefits of staying in the handcuffed position. While the current occupation may not be optimal, there is not enough distress to proactively break out of the handcuffs and pursue something else in the beta region, which results in the blind commitment to the current non optimal status quo. Additionally, this relation between the alpha and beta regions is not as direct- the beta region is not an illustratable linear function, but one with stochastic and unknown properties. It is not known whether there the beta region is actually more optimal than the alpha region; only the current circumstance of the alpha region is known. This makes the prospect of breaking out more painful.

To say there is one solution to the Golden Handcuff dilemma is foolish- everyone has different circumstances and weighs priorities differently. Perhaps interest in work is not important while the outsized compensation is. Staying handcuffed is not necessarily a bad thing- just maybe sub optimal depending on the unknown beta region possibilities.

Regardless of whatever the opinion is, it is critical to acknowledge the situation and make a deliberate decision- to stay or to go- for the regret experienced moments prior to death is something no one wants to face.