Why Do I Want Money?

An unsuccessful deliberation behind the desire for more money

When thinking of the next step in my career, I can’t seem to out wrestle the inherent desire for more income. While the lust for a higher salary seems very self explanatory and any analysis beyond a simple retort “who doesn’t” may be sufficiently overthinking, I cannot help but wonder why I constantly think about a next profession solely in the frame of income.

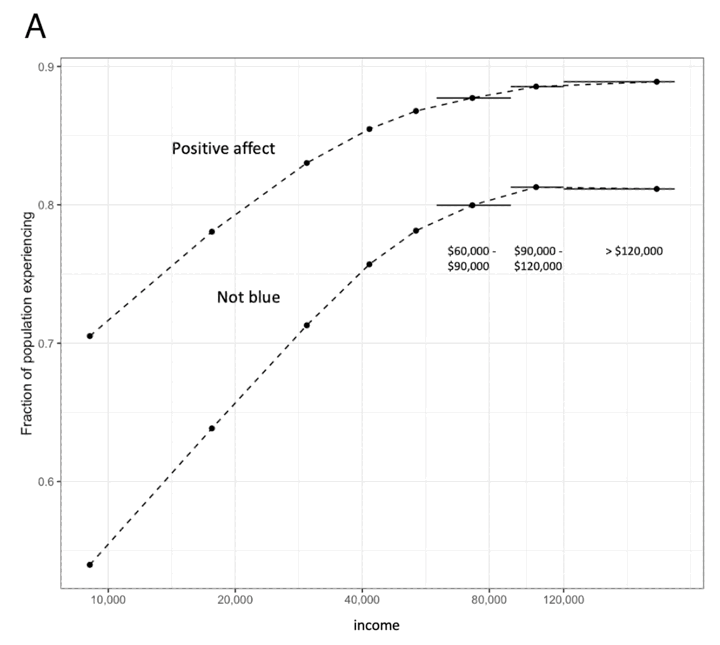

The desire for more money is pretty self explanatory. Presumably, more money results in a higher probability of happiness and a richer (no pun intended) life- new experiences are afforded and fundamental stresses (food, water, rent) are mitigated. If the input to acquire money is constant (usually never the case), more money is better. This is often represented in literature with permutations of a “Can Money Buy Happiness” study referencing a monotonically increasing logarithmic relation between income and happiness (“Positive affect”) and non-sadness (“Not blue”) such as below. Increased income results in greater diminishing happiness.

Human nature is another explanation of my monetary incentives. Being social creatures, humans tend to be status seeking. Similar to how peacocks grow luscious feathers to determine a hierarchy of status, we strive to distinguish ourselves as having more status through whatever instruments available, ranging from the number of followers (high schoolers in the social media age) to the size of yams (the natives of the Pohnpei Micronesia). Perhaps the ultimate signal of status is money: the perfectly quantitative and universally comparable metric of net worth. More money signals higher status and I am unabashedly human.

While these general explanations may be what is occurring deep in my psyche, I feel uneasy to rest the explanations- there are too many arguments for the contrary.

For starters, from the various “Can Money Buy Happiness” studies, there are diminishing returns of happiness after an income of about $80,000 (+ some inflation adjustment), such that a consistent doubling of income is required to reach a same amount of happiness gain. This means the happiness increase from a raise of $60,000 to $120,000 is the same as that from a raise of $120,000 to $240,000 and $240,000 to $480,000. A question of “is the significantly increasing amount of effort, sacrifice, and time investment worth the happiness gain?” is to be answered here.

When we look into life’s macro, the main driver for happiness never seems to be money; in fact, the longest longitudinal study in happiness (detailed by Dr. Waldinger and Dr. Schulz in The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness) cited relationships and the minimization of loneliness as the main drivers for happiness. Oddly enough, the greed for money seems to contradict this fact: a higher income usually results in a trade of free time connecting with loved ones. The trope of the rich lonely successful business person is certainly not for no reason. Anecdotally, the preference for companionship over income is further depicted beautifully by If I Knew Then, a compilation of insights gleamed over 50 years by the 1963 Harvard Business School grads. When asked if financial wealth is a yardstick for success, the consensus of money is that it is nothing but a minor metric, diminutive against the factors of family, purpose, impact, and charity. If these are realizations made by those with some of the greatest instincts for the archetypal “money, position, and power,” I surely would have similar realizations 50 years from now.

My own life follows a similar narrative as well. When I think about the outlier moments of immense happiness, I think of the times immediately following vastly uncertain and hard fought achievement. Some instances are: receiving university offers in high school, reaching a certain rank in my major, landing an offer at my first software job, and competing in my first powerlifting meet. Moments of happiness also arise in the midst of new experiences: moving to New York for the first time, travelling to Italy, France, Korea, and Japan, meeting new friends, and entering new relationships. None of these instances directly indicate more money = more happiness, though some implicitly require money to be spent.

Perhaps a better way to frame the money-happiness question: “how much money do I need to find the areas which draw me immense happiness?” and “how much more money, if any, do I need to experience more instances of immense happiness?”

There is a catch, however. As briefly touched on earlier, income and additional income do not come for free; there is some trade off given for more income. The most obvious is time. Other tradeoffs are more subtle: stress, energy outside of work, cynicism and optimism, complacency, and, the most striking, happiness. This poses a contradictory result: by trading these aspects of my life, I am earning a higher income, which is supposed to offer me those aspects I traded off in the first place. In that case, why not save all my energy, not pursue the tradeoff in the first place, and simply experience a less stressful and happy life with what I currently have? (Parable of the Mexican Fisherman applies here!)

Despite all the rigorous studies read and the anecdotal stores of regret and wisdom absorbed, I still can’t seem to answer that question. Why not just be content? I’m not sure. Maybe it’s the primitive hardwired intuition of accumulating resources or the fundamental pursuit of status that’s driving my actions. Whatever it is, I have a sense of acceptance in my path, best summarized by Naval Ravikant:

“It’s easier to fulfill your material needs than to renounce them.”

this was a great read! I often think about the dread that the pursuit of comfort (money, love, etc) plagues my day to day